Football at all levels, whether high school, college, or professional, is driven by offense. We are seeing the game evolve to more wide open offenses. Defense is reeling. In the NFL, successful head coaches are being fired because their offenses struggled, even if their defenses, and teams, were quite successful. Teams are turning to hotshot college coaches like Chip Kelly and even CFL coaches like Marc Trestman because of their offensive expertise.

What's a defensive coach to do?

Part of it must be a change in mentality. The defense needs to dictate what the offense will do, and change those looks frequently. It needs to confuse offensive linemen and quarterbacks, and be unpredictable. It must affect the quarterback while remaining sound in coverage.

Sounds like a lot, and it is. However, we feel we have a great way to do those things with a concept called fire zones. Fire zones are not new to the game, but they are underutilized, in my opinion, and not as creative as they could be.

Perhaps the man most noted for this concept is Manny Diaz, the defensive coordinator for the Texas Longhorns. Diaz came under fire this year for a lackluster Texas defense, but this season was an aberration. Diaz had stops as a defensive coordinator at Mississippi State and Middle Tennessee State before arriving at Texas, and is considered one of the top up-and-coming defensive minds in the game. Manny likes to use different fronts and stand up different guys for maximum confusion, and the rules are sound.

Brophy Football explains in detail Manny Diaz's

philosophy. It is somewhat long, so get to it when you have time.

Why Fire Zones?

A fire zone, by definition, is a three deep, three underneath zone that blitzes five defenders. The five blitzers are limited only by your imagination.

We like to run fire zones out of a 3-4 alignment with a Cover 2 shell. For us it is a Cover 2 shell with a 3-4 alignment, but you can run it out the 4-3, Stack, 4-2-5 or even Bear fronts. Joe Daniel of football-defense.com does a

great job of explaining fire zones out of the 4-3. We like these out of a 3-4 because they give our linemen better angles to blitz and contain rush.

There are two benefits to fire zones. One, it reduces how much thinking a defender has to do, because the presnap read gives him his postsnap response. Two, it confuses the read of the offensive linemen and the quarterback. Let me explain.

The three-deep defenders should respond the same way every time. Run or pass, drop to your deep zone until you are absolutely certain it is a run, and then rally to the ball. There is always Cover 3 over the top. We should never ever get beat deep on a fire zone. Fire zones are quite safe. We can get burned by play action, but there should never a huge gash play if our defenders execute their assignment.

Typically, in any given defensive scheme, defenders must read their keys.Keys are indicators that a play is either a run or pass and where it is going. The linebackers first key is the guard across from them. If the guard comes low and hard, the linebacker knows the play is a run. If the guard comes out high and sets back, he knows the play is a pass. As far as other positions go, defensive linemen key the offensive lineman across from them, safeties key the offensive tackles, and corners key the receiver in front of them, typically. But in fire zones, players don't have to read their usual keys; their response postsnap is determined by their presnap read.

Presnap dictates postsnap

Let's start with the three underneath defenders, those assigned to Hot 2 and Hot 3. Presnap, the defender needs to assess whether his designated man is a run or pass threat, and that will determine his postsnap response. The defender's man is determined by counting, starting from his left, the skill players. Hot 2 is looking for the #2 player on his side to determine his response, while Hot 3 is looking for the #3 player on his side. See the diagrams below for examples.

The defender must asses whether his defender is run threat or pass threat. A pass threat is defined as anyone in a two-point stance that is not in the backfield. So this includes wide receivers, flexed tight ends, etc. A run threat is defined as anyone in a three-point stance or in the backfield, so tight ends and running backs, essentially.

If the underneath defender's man is a pass threat, the defender backpedals to his landmark regardless of what the offense does. The Hot 2 to the boundary will back pedal 5-8 yards to the boundary hash. The Hot 2 to the field will back pedal the same distance to the field hash, and the Hot 3 will back pedal 5-8 yards to roughly the middle of the field. This is to take away any hot slants over the middle. If the quarterback continues to hold the ball, the linebackers will continue to drop to 8-12 yards and break on any ball thrown.

If the defender's man is a run threat, his response changes. Now he is primarily a run player. On the snap of the ball, he does not drop to his landmark. He stays at his presnap alignment, watching the backfield. If the quarterback hands off, he attacks the line of scrimmage. The Hot 2 player attempts to keep the runner inside his outside shoulder, pushing him back to the Hot 3 player. The Hot 3 player attempts to push the runner to the runside Hot 2 player, working inside-out. They want to work together to keep the back pinned in. If the quarterback drops to pass, then both Hot 2 and 3 players work to reach their landmark.

Fire zone responses

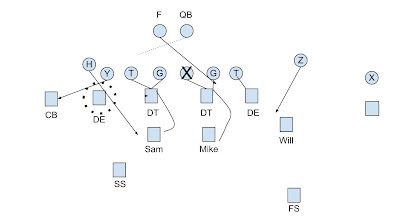

This shows what a fire zone spread response would be. Notice, the fire zone here is field scrape, but the rules are the same for every Hot 2 and Hot 3 defender. The linemen on both sides have been removed for clarity, as well as the two corners and a safety.

As you can see, the Hot 2 defenders are matched up with pass threats, so they must drop regardless. The Hot 3 defender will watch the backfield and attack if it is run. If it is a pass, he drops.

Because defenders do not need to "read" in the typical way, it allows players to react quicker, play fast and run quickly to the ball.

How to blitz

It's important to note as well that a fire zone does not necessarily account for every gap, but it does account for open spaces. If the gap is jammed up with offensive linemen, why try to force a player through that gap? The running back is looking for open space; if we insert our defenders in those spaces, then we should be in great position to make a play. If the guard turns to the stud, then the stud works across his face. If the guard turns away, then the stud goes right off his butt, straight to the ball carrier or quarterback.

Notice, the guard turns toward the end and nose guard, and they work to fight across his face, to grass.

Notice, the guard turns away from the end and nose guard, and they cut right off his butt.

These blitzes most certainly needs repetitions in practice. If the pressure does not get home a good amount of time, there are holes in the coverage. So rep this again and again to make sure you covering all the open grass.

Examples

Our favorite fire zone is field scrape. We try to put our best defenders to the wide side of the field, because that is where the most space is. What is the offense's goal? Put its best players in space. As a defense, we want our best players defending the most space. However, you can run this to the boundary, to the running back, to the tight end.

Now, you can run fire zones out of a variety of fronts. For us it is a Cover 2 shell with a 3-4 alignment, but you can run it out the 4-3, Stack, 4-2-5 or even Bear fronts. Primarily, despite our Cover 2 shell, we are a Cover 3 team, usually dropping down one of the safeties for Hot 2 responsibility. Our Sam, on the field side, is better at coverage than our Liz, so we take that into consideration when calling these fire zones.

This is field scrape, meaning we run this from the field side. Note that our End is on a contain rush, working upfield and outside all the action.

|

| Field Scrape |

The counterpart to Scrape is Mix. You run it almost exactly the same way, but with the Mike and Stud switching responsibility. This confuses the offensive linemen and it doesn't take much work from your players.

|

| Field Mix |

We also like the fire zone Gut. This gives us great vertical pressure while remaining sound in coverage. It does give us two players on contain rushes that are slower, but if they can force any action back inside, we should be fine.

|

| Mike goes first, Will goes second |

These are a few examples of fire zones that we like; however, get creative. You can really bring or drop any defenders. You could bring a safety on a blitz, or drop a lineman into coverage. It really is up to you, you just have to plug in the rules and go!

Now, fire zones are not without limits. Quick hitches, screens, any passes to the sideline can hurt this defense. If your blitz doesn't get there, you can be exposed in coverage. and if you run away from the blitz, your players have to sound. But that's why you rep this constantly, and it can be repped in groups or even individual time, without taking away team time. It really is a solid scheme!

Next week I will take a look at how fire zones can stop different zone read and option attacks, specifically what the 49ers are doing in the NFL. The rules are likeable and learnable and can stop attacks in their tracks. If you have any questions are comments, feel free to leave one or follow me on Twitter

@Coach_JPhillips. God bless and have a great day!